The Moon has orbited Earth for 4.5 billion years, likely forming from a collision between our planet and a Mars-sized body known as Theia.

Over time, however, the Moon’s orbit has gradually changed, and it is now slowly drifting away from Earth at a rate of about 3.8 centimeters (1.5 inches) per year.

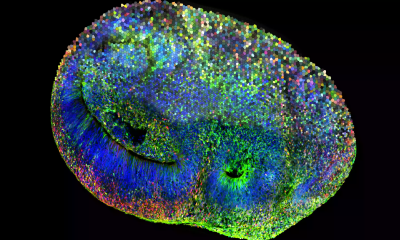

This precise measurement comes from the Lunar Laser Ranging Experiment. During the Apollo missions of the 1960s and 1970s, astronauts placed reflectors on the Moon’s surface. By sending lasers to these reflectors and timing how long the light takes to return, scientists can measure the distance to the Moon with an accuracy of around 3 centimeters (1.2 inches). Repeated measurements confirm the Moon’s gradual recession.

Projecting this rate backward, the Moon would have collided with Earth about 1.5 billion years ago—a contradiction, since the Moon is known to be much older. Researchers instead study rock and coral layers to estimate historical distances and the length of Earth days, providing a clearer picture of the Moon’s orbit over time.

Looking forward, this slow drift will eventually end humanity’s ability to witness total solar eclipses. “Over time, the number and frequency of total solar eclipses will decrease,” NASA lunar scientist Richard Vondrak said in 2017. “About 600 million years from now, Earth will experience a total solar eclipse for the last time.”

The current ability of the Moon to completely cover the Sun is a cosmic coincidence: the Sun is roughly 400 times farther from Earth than the Moon and about 400 times larger in diameter. Four billion years ago, before the Moon reached its present orbit, it would have appeared roughly three times larger in the sky.

Although the Moon will continue to drift outward and appear smaller over time, it will remain gravitationally bound to Earth. By the time the Sun expands into a red giant, it will engulf Earth before the Moon can ever escape, ensuring that the two celestial bodies remain linked until the very end.

-20260222063838.webp)

-20260206050656.webp)