I know, you probably haven't even driven one yet, let alone seriously contemplated buying one, so the prediction may sound a bit bold, but bear with me.

We are in the middle of the biggest revolution in motoring since Henry Ford's first production line started turning back in 1913.

And it is likely to happen much more quickly than you imagine.

Many industry observers believe we have already passed the tipping point where sales of electric vehicles (EVs) will very rapidly overwhelm petrol and diesel cars.

It is certainly what the world's big car makers think.

Jaguar plans to sell only electric cars from 2025, Volvo from 2030 and last week the British sportscar company Lotus said it would follow suit, selling only electric models from 2028.

And it isn't just premium brands.

General Motors says it will make only electric vehicles by 2035, Ford says all vehicles sold in Europe will be electric by 2030 and VW says 70% of its sales will be electric by 2030.

This isn't a fad, this isn't greenwashing.

Yes, the fact many governments around the world are setting targets to ban the sale of petrol and diesel vehicles gives impetus to the process.

But what makes the end of the internal combustion engine inevitable is a technological revolution. And technological revolutions tend to happen very quickly.

This revolution will be electric

Look at the internet.

By my reckoning, the EV market is about where the internet was around the late 1990s or early 2000s.

Back then, there was a big buzz about this new thing with computers talking to each other.

Jeff Bezos had set up Amazon, and Google was beginning to take over from the likes of Altavista, Ask Jeeves and Yahoo. Some of the companies involved had racked up eye-popping valuations.

For those who hadn't yet logged on it all seemed exciting and interesting but irrelevant - how useful could communicating by computer be? After all, we've got phones!

But the internet, like all successful new technologies, did not follow a linear path to world domination. It didn't gradually evolve, giving us all time to plan ahead.

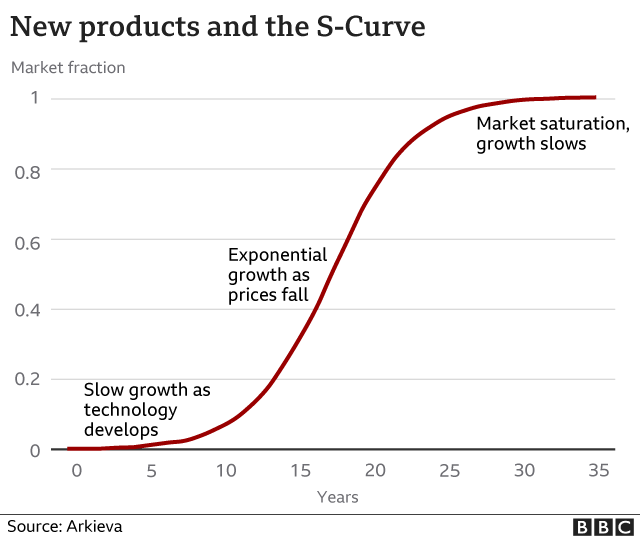

Its growth was explosive and disruptive, crushing existing businesses and changing the way we do almost everything. And it followed a familiar pattern, known to technologists as an S-curve.

Riding the internet S-curve

It's actually an elongated S.

The idea is that innovations start slowly, of interest only to the very nerdiest of nerds. EVs are on the shallow sloping bottom end of the S here.

For the internet, the graph begins at 22:30 on 29 October 1969. That's when a computer at the University of California in LA made contact with another in Stanford University a few hundred miles away.

The researchers typed an L, then an O, then a G. The system crashed before they could complete the word "login".

Like I said, nerds only.

A decade later there were still only a few hundred computers on the network but the pace of change was accelerating.

In the 1990s the more tech-savvy started buying personal computers.

As the market grew, prices fell rapidly and performance improved in leaps and bounds - encouraging more and more people to log on to the internet.

The S is beginning to sweep upwards here, growth is becoming exponential. By 1995 there were some 16 million people online. By 2001, there were 513 million people.

Now there are more than three billion. What happens next is our S begins to slope back towards the horizontal.

The rate of growth slows as virtually everybody who wants to be is now online.

Jeremy Clarkson's disdain

We saw the same pattern of a slow start, exponential growth and then a slowdown to a mature market with smartphones, photography, even antibiotics.

The internal combustion engine at the turn of the last century followed the same trajectory.

So did steam engines and printing presses. And electric vehicles will do the same.

In fact they have a more venerable lineage than the internet.

The first crude electric car was developed by the Scottish inventor Robert Anderson in the 1830s.

But it is only in the last few years that the technology has been available at the kind of prices that make it competitive.

The former Top Gear presenter and used car dealer Quentin Willson should know. He's been driving electric vehicles for well over a decade.

He test-drove General Motors' now infamous EV1 20 years ago. It cost a billion dollars to develop but was considered a dud by GM, which crushed all but a handful of the 1,000 or so vehicles it produced.

The EV1's range was dreadful - about 50 miles for a normal driver - but Mr Willson was won over. "I remember thinking this is the future," he told me.

He says he will never forget the disdain that radiated from fellow Top Gear presenter Jeremy Clarkson when he showed him his first electric car, a Citroen C-Zero, a decade later.

"It was just completely: 'You have done the most unspeakable thing and you have disgraced us all. Leave!'," he says. Though he now concedes that you couldn't have the heater on in the car because it decimated the range.

How things have changed. Mr Willson says he has no range anxiety with his latest electric car, a Tesla Model 3.

He says it will do almost 300 miles on a single charge and accelerates from 0-60 in 3.1 seconds.

"It is supremely comfortable, it's airy, it's bright. It's just a complete joy. And I would unequivocally say to you now that I would never ever go back."

We've seen massive improvements in the motors that drive electric vehicles, the computers that control them, charging systems and car design.

But the sea-change in performance Mr Willson has experienced is largely possible because of the improvements in the non-beating heart of the vehicles, the battery.

The most striking change is in prices.

Just a decade ago, it cost $1,000 per kilowatt hour of battery power, says Madeline Tyson, of the US-based clean energy research group, RMI. Now it is nudging $100 (£71).

That is reckoned to be the point at which they become cheaper to buy than equivalent internal combustion vehicles.

But, says Ms Tyson, when you factor in the cost of fuel and servicing - EVs need much less of that - many EVs are already cheaper than the petrol or diesel alternative.

At the same time energy density - how much power you can pack into each battery - continues to rise.

They are lasting longer too.

Last year the world's first battery capable of powering a car for a million miles was unveiled by the Chinese battery maker, CATL.

Companies that run big fleets of cars like Uber and Lyft are leading the switchover, because the savings are greatest for cars with high mileage.

But, says Ms Tyson, as prices continue to tumble, retail customers will follow soon.

How fast will it happen?

The answer is very fast.

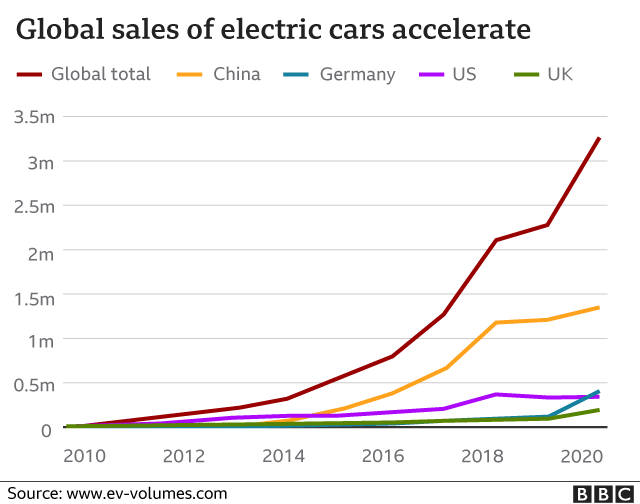

Like the internet in the 90s, the electric car market is already growing exponentially.

Global sales of electric cars raced forward in 2020, rising by 43% to a total of 3.2m, despite overall car sales slumping by a fifth during the coronavirus pandemic.

That is just 5% of total car sales, but it shows we're already entering the steep part of the S.

By 2025 20% of all new cars sold globally will be electric, according to the latest forecast by the investment bank UBS.

That will leap to 40% by 2030, and by 2040 virtually every new car sold globally will be electric, says UBS.

The reason is thanks to another curve - what manufacturers call the "learning curve".

The more we make something, the better we get at making it and the cheaper it gets to make. That's why PCs, kitchen appliances and - yes - petrol and diesel cars, became so affordable.

The same thing is what has been driving down the price of batteries, and hence electric cars.

We're on the verge of a tipping point, says Ramez Naam, the co-chair for energy and environment at the Singularity University in California.

He believes as soon as electric vehicles become cost-competitive with fossil fuel vehicles, the game will be up.

That's certainly what Tesla's self-styled techno-king, Elon Musk, believes.

Last month he was telling investors that the Model 3 has become the best-selling premium sedan in the world, and predicting that the newer, cheaper Model Y would become the best-selling car of any kind.

"We've seen a real shift in customer perception of electric vehicles, and our demand is the best we've ever seen," Mr Musk told the meeting.

There is work to be done before electric vehicles drive their petrol and diesel rivals off the road.

Most importantly, everyone needs to be able charge their cars easily and cheaply whether or not they have a driveway at their home.

That will take work and investment, but will happen, just as a vast network of petrol stations rapidly sprang up to fuel cars a century ago.

And, if you are still sceptical, I suggest you try an electric car out for yourself.

Most of the big car manufacturers now have a range of models on offer. So take one for a test drive and see if, like Quentin Willson, you find you want to be part of motoring's future.

Source: BBC

-20260103050848.jpg)

-20260106082251.webp)

-20260106073954.webp)

-(2)-20260102070806.jpeg)

-(25)-20251122062715-20260105041159.jpeg)

-20260103102222.webp)