Researchers at the University of California, Santa Cruz have successfully trained lab-grown brain organoids to solve a classic engineering challenge known as the inverted pendulum or cart-pole problem, marking the first rigorous academic demonstration of goal-directed learning in brain organoids.

The cart-pole problem is often compared to balancing a ruler vertically in the palm of one’s hand, where constant attention and small adjustments are needed to keep it upright. In engineering, robotics and artificial intelligence, it is widely used as a benchmark to test whether a control system can learn, adapt and respond effectively to changing information. Every human infant, researchers note, must solve a similar problem while learning to stand and walk.

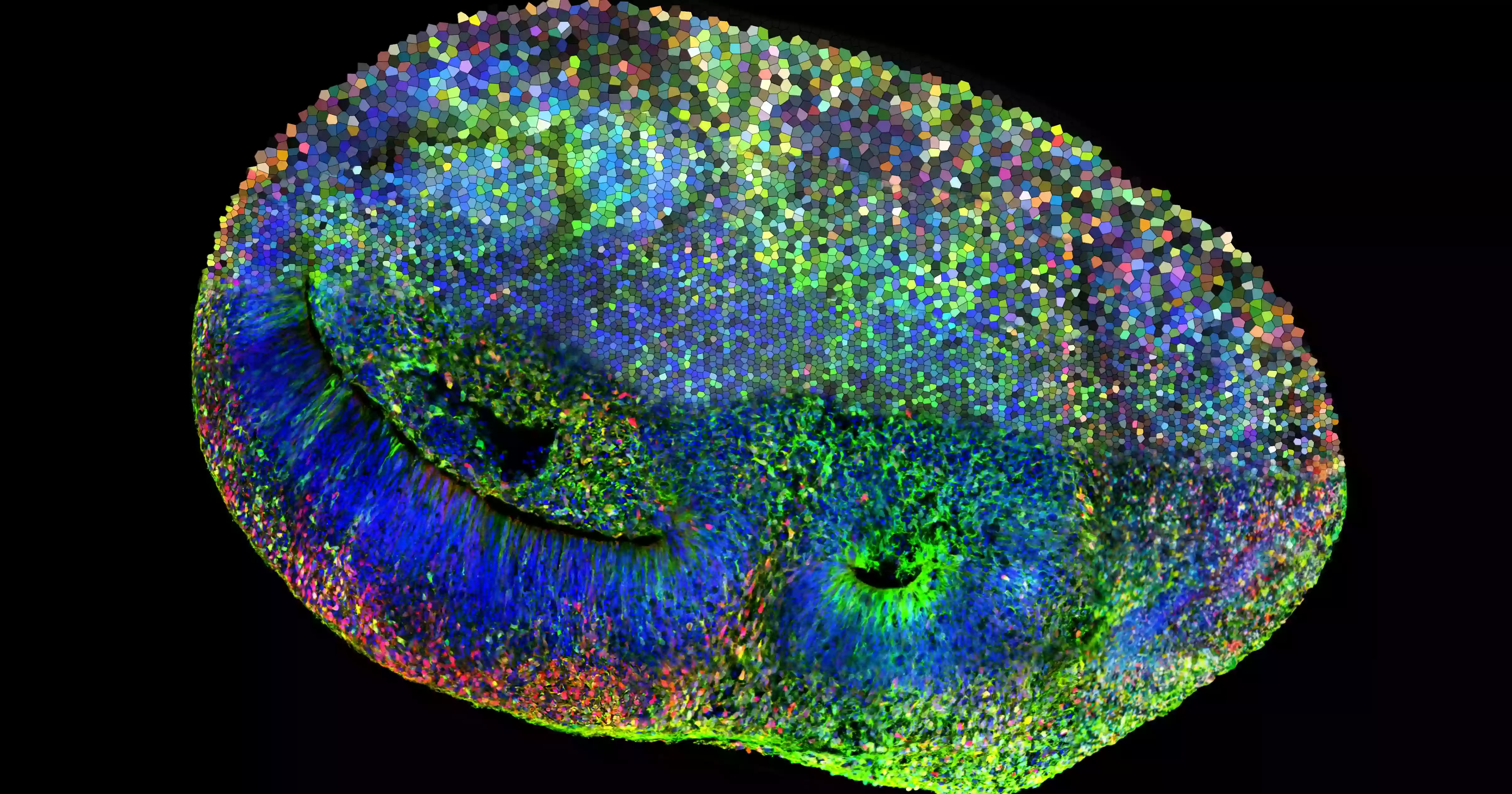

In the new study, scientists trained tiny pieces of brain tissue grown in the laboratory, known as brain organoids, to balance a virtual pole by sending and receiving electrical signals. The work was led by Ash Robbins, a PhD student in electrical and computer engineering at UC Santa Cruz’s Baskin School of Engineering, alongside Professor Mircea Teodorescu and Distinguished Professor of Biomolecular Engineering David Haussler. Their findings were published in the journal Cell Reports.

The research aims to better understand how neurons transmit information through electrical spikes in ways that allow learning and improvement. Such insights could help scientists study how neurological conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, stroke, concussion, autism, schizophrenia, Parkinson’s disease, dyslexia and ADHD alter the brain’s ability to learn.

“We are trying to understand the fundamentals of how neurons can be adaptively tuned to solve problems,” Robbins said. “If we can figure out what drives that in a dish, it gives us new ways to study how neurological disease can affect the brain’s ability to learn.”

Brain organoids are small, three-dimensional tissues grown from stem cells that mimic early brain development, structure and function. Although smaller than a peppercorn, they can contain networks of several million neurons. For about 15 years, organoids of different organs have been widely used in biomedical research, but only recently have scientists begun exploring how brain organoids might be used to study learning.

In this study, the researchers placed mouse-derived brain organoids on a specialized chip that allows them to record electrical activity from neurons and stimulate selected cells. Using electrical signals of varying strength, the team conveyed information about the angle of a virtual pole as it tipped in one direction or the other. In response, the organoid produced electrical activity that was translated into forces applied to the virtual cart, helping to balance the pole.

Each attempt to balance the pole was treated as an episode. When the pole fell, the episode ended and a new one began. The goal was to keep the pole upright for as long as possible, similar to playing a video game.

The organoid’s performance was evaluated in five-episode blocks. If its average performance over the most recent five episodes improved compared with the previous 20, no training signal was given. If performance did not improve, a training signal was applied. Importantly, this feedback was only delivered after an episode ended, not while the organoid was actively balancing the pole.

An artificial intelligence method known as reinforcement learning was used to decide which neurons received training signals. Robbins compared the process to having an artificial coach that tells the system it is doing something wrong and nudges it to adjust.

The results showed clear improvement. Organoids trained with adaptive reinforcement learning achieved a 46 percent “winning” rate, defined by a minimum time threshold for balancing the pole. In contrast, organoids that received random training signals achieved only a 4.5 percent winning rate.

“When we can actively choose training stimuli, we can actually shape the network to solve the problem,” Robbins said. “What we showed is short-term learning. We can consistently shift an organoid from one state into another that we are aiming for.”

However, the learning did not last. After about 15 minutes of training, the organoids were allowed to rest for 45 minutes. Following this rest period, performance dropped back to baseline, suggesting the organoids forgot most of what they had learned.

Haussler said this limitation may be overcome in the future by developing more complex organoids. He suggested that tissues incorporating multiple brain regions involved in learning might be needed to reproduce the kind of long-term learning seen in animals.

Independent experts say the findings are significant. Keith Hengen, an associate professor of biology at Washington University in St. Louis who was not involved in the research, said the study shows that even minimal neural circuits can be guided toward solving real control problems when given targeted electrical feedback.

“These are incredibly minimal neural circuits. There is no dopamine, no sensory experience, no body to sustain, no goals to pursue,” Hengen said. “Yet the tissue is plastic and structured enough to be pushed toward adaptive computation. This suggests that the capacity for learning is intrinsic to cortical tissue itself.”

The research team, part of the Braingeneers group within the UC Santa Cruz Genomics Institute, drew inspiration from earlier work conducted decades ago at Caltech and Georgia Tech by scientist Steve Potter. They used an electrophysiology system developed with industry partners at Maxwell Biosciences to communicate electrically with the organoids.

From an engineering perspective, Professor Teodorescu said the study is powerful because it combines measurement, stimulation and adaptation in a single closed-loop system. He noted that this allows researchers to study learning as a physical process, something that is very difficult to do in intact brains.

To support further research, Robbins developed an open-source software platform called BrainDance. The tool is designed to allow biologists to run complex neural learning experiments with organoids without needing to build custom games, hardware interfaces or training environments.

“This software makes running very complicated experiments extremely easy,” Robbins said, adding that labs typically spend years developing such systems on their own.

Haussler emphasized that the goal of the research is to advance understanding of the brain and improve treatment of neurological diseases, not to replace traditional computers or robotic controllers with lab-grown brain tissue. He cautioned that such applications, especially involving human brain organoids, would raise serious ethical concerns.

The researchers now plan to investigate why their coaching method works, which neurons are most effective to target, what kinds of training signals are best, and how long-term learning might eventually be achieved in lab-grown brain tissue.

#From News-Medical

-20260206050656.webp)

-20260203061855.webp)

-20260220065859.jpeg)

-20260219110716.webp)

-20260219054530.webp)