In the aftermath of the overthrow of Bangladesh’s long-serving leader, Sheikh Hasina, a political vacuum has paved the way for the resurgence of Islamist extremism. Across the country, hardline religious groups are making bold moves to assert their influence. They are challenging the country`s fragile democracy and secular principles, according to a report in the US-based newspaper The New York Times.

In one city, religious fundamentalists have declared that young women can no longer play football. In another incident, a man was arrested for harassing a woman for adjusting her headscarf or not wearing a hijab. Police were later forced to release him and he was later felicitated with a garland of flowers in the court premises.

The demands have grown more aggressive. At a rally in the capital, Dhaka, demonstrators warned that if the government did not impose the death penalty on anyone who disrespects Islam, they would carry out executions themselves. Days later, an outlawed group marched through the streets, demanding an Islamic caliphate.

After 15 years of Sheikh Hasina’s rule—marked by both a crackdown and appeasement of Islamist forces—radical elements are now stepping into the political void. While she suppressed extremist groups, she also sought to win over religious conservatives by allowing thousands of unregulated Islamic seminaries and investing $1 billion in mosque construction.

Now, with her departure, both fringe extremist groups and more mainstream Islamist parties are aligning in pursuit of a more religiously governed Bangladesh.

"We were at the forefront of the protests. We protected our brothers on the street," said Sheikh Tasnim Afroz Emi, 29, a sociology graduate from Dhaka University "Now after five, six months, the whole thing turned around"

Critics say the country`s interim government, led by Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus, 84, has not pushed back hard enough against extremist forces. They accuse Yunus of being soft, lost in the weeds of democratic reforms, conflict-averse and unable to articulate a clear vision as extremists take up more public space.

Nahid Islam, a student leader who was a government minister in Bangladesh`s interim administration before stepping away recently to lead a new political party, acknowledged "the fear is there" that the country will slip toward extremism.

In the rebuttal statement, the chief adviser`s press secretary stated that it is crucial to acknowledge Bangladesh`s progress over the last year and the complexity of the situation rather than relying on selective, incendiary examples that paint an inaccurate picture.

Criticising the report, Shafiqul said while the article highlights certain incidents of religious tension and conservative movements, it overlooks the broader context of progress.

"Bangladesh has made substantial strides in improving the conditions for women, and the interim government has been particularly committed to their security and well-being," Shafiqul said.

The press secretary also noted that the interim government has prioritised women`s rights and security. This focus stands in stark contrast to the bleak image painted in the NY Times article.

He also gave an example of "Youth Festival 2025," where nearly 2.7 million girls from all corners of the country participated in 3,000 games and cultural activities.

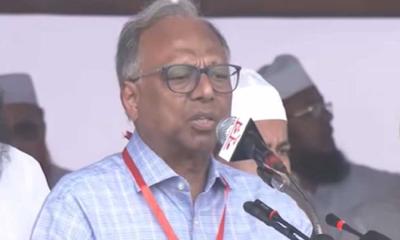

The largest Islamist party, Jamaat-e-Islami, sees an opportunity. Though unlikely to win upcoming elections, the party aims to capitalize on the weakening of major secular parties. "Islam provides moral guidance for both men and women regarding behavior and ethics," said Mia Golam Parwar, the party’s secretary-general. "Within those guidelines, women can participate in any profession—sports, singing, theater, judiciary, military, and bureaucracy."

However, on the ground, interpretations of Islamic governance are taking a harsher turn.

In Taraganj, a small agricultural town, a football match was organized for young women to promote sports among girls. But as preparations were underway, a local mosque leader, Ashraf Ali, declared that women should not be allowed to play. He launched a campaign against the game, broadcasting warnings via loudspeakers.

Authorities caved to the pressure, canceling the match and imposing restrictions on the area. Aktar, a 22-year-old player who had traveled for hours to participate, described the tense scene: "There were many cars, the army, and police telling us the match was canceled."

Organizers hoped to reschedule, but Mr. Ali’s persistent threats left them uncertain. "I would rather become a martyr than allow the match," he had declared, boasting about his success in stopping the event.

Women’s football is not his only target. Mr. Ali has also led campaigns against the Ahmadiyya, a minority Muslim community that has long faced persecution in Bangladesh. The night Sheikh Hasina’s government fell, mobs attacked Ahmadiyya places of worship as part of a wave of religious violence that also targeted Hindu temples.

Even now, the community remains under threat. Their prayer hall’s damaged sign cannot be restored, and they are forbidden from broadcasting their call to prayer. Mr. Ali, dismissing any role in the violence, continues to preach that the Ahmadiyya must be expelled.

"The public is respectful," said A.K.M. Shafiqul Islam, president of the local Ahmadiyya chapter. "But these religious leaders are against us."

As Bangladesh attempts to restore democracy, extremist groups are leveraging instability to push their agenda, posing a grave challenge to the nation’s secular fabric.