In Dhaka, the street art is still visible: a cuffed hand clenched in a fist; an injured student being rushed towards aid on a bicycle; the words “the blood of martyrs shall not go in vain”.

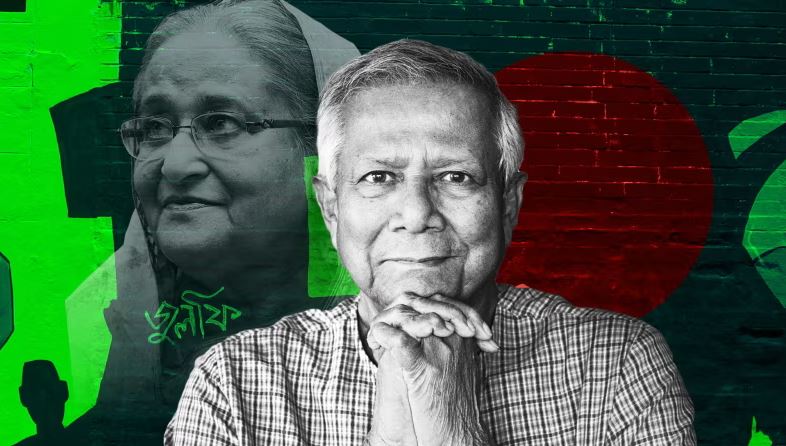

These murals were daubed in July and August, after police opened fire on people who had gathered to protest against a job scheme favouring Bangladesh’s ruling Awami League party. With hundreds dead, students from Dhaka University seized control of the uprising and forced the country’s authoritarian ruler, Sheikh Hasina, to flee to India. It has been one of the most striking victories for people power of recent times.

The three months since what the students call a “revolution” have been equally extraordinary. In August, they invited Muhammad Yunus, the 84-year-old Nobel peace prizewinning economist and entrepreneur, to serve as “chief adviser”, in effect caretaker leader. Yunus has embarked on a sweeping reform of Bangladesh’s broken political system and institutions. Elections are promised at a yet-to-be defined point in the future. And the students sit in a privileged place, with two holding cabinet positions in the interim government. Yunus insists he has no ambition to continue in politics after his current role.

When he meets world leaders, Yunus presses upon them a recently published book featuring Dhaka’s protest art. “They are the heroes of the country,” Yunus says of the students in an interview with the Financial Times. “They are the winners . . . The revolution was brought by them.”

In vigour and ambition, the changes Yunus and his young government are attempting are of a type unseen until now in South Asia’s hidebound politics — analogous to reforms that began in central Europe following the collapse of the Soviet bloc in 1989, or Myanmar’s decade-long break with military rule after 2011.

Yunus, who accuses the Awami League of espousing “fascism” because of its co-opting of institutions like the police and the courts, has convened reform commissions tasked with remaking compromised arms of the state. These range from reshaping the country’s constitution and election system to attempting to account for the hundreds — possibly thousands — of people who, according to human rights groups, were tortured or killed in secret prisons during the regime. The commissions have been tasked with reporting back by the end of the year.

Meanwhile, a newly installed central bank governor, Ahsan Mansur, is tracking down and trying to recover some $17bn he estimates was taken abroad by bank owners close to the old regime — just one part of the massive corruption Hasina and her associates have been accused of.

It’s a moment rich with promise, but fraught with risks for the leader and his small team — and a gamble, too, for one of the world’s most populous countries, whose political journey after independence in 1971 has often been bumpy.

Time is short, and much could yet go wrong. Protesters are continuing to rally in Dhaka’s streets, last week demanding the resignation of the president, Mohammed Shahabuddin, who was installed by the old regime. And the country is still recovering from the chaotic days after August 5, when many Awami League supporters were arrested, attacked or killed.

Some of those targeted were minority Hindus, angering the ruling establishment in India, which has historically supported the Awami League. Bangladesh’s most important foreign partner has remained hostile to what a broad swath of the Indian establishment insists was US-backed regime change. And Islamists, freed from the oppression of the old regime, are beginning to reassert themselves. Some favour the imposition of sharia law, or even the creation of a Bangladeshi caliphate.

There have been implications for Bangladesh’s economy, too. The uprising caused some global retailers to divert orders from what is now the world’s second-largest garment industry, calling into question the future of a sector that has helped lift Bangladesh’s economy out of the ranks of the world’s poorest countries and now employs millions of women.

There are broader questions too. How long will the students remain in government? Should only police be prosecuted for the summer’s bloodshed, or civilians too? Should the Awami League, the country’s biggest and oldest political party, thought to have the allegiance of tens of millions, be allowed to run for office again? In other words, is the “revolution” meant to be permanent?

Yunus insists the students “didn’t have any plans to take over the government”, but “were simply making some very modest demands, which turned into a revolution”.

Asif Mahmud — a 26-year-old former Dhaka University linguistics student who is now minister for youth, sports and labour — says their work is far from finished. “The revolution is not over yet,” he says.

“It is a continuous process,” he adds. “This mandate has to be fulfilled.”

In the hours following Hasina’s overthrow on August 5, student leaders approached Yunus, a former economics professor turned microfinance pioneer, and put him forward as their choice for chief adviser. A few days later, he was on a plane back to Dhaka from Paris, where he’d been receiving medical treatment.

The founder of Grameen Bank, which specialises in microloans to the working poor, Yunus won the Nobel peace prize in 2006. In the years since, his name had resurfaced periodically as a potential leader. As well as having a strong international reputation, he was also seen to be above the battles between Bangladesh’s bitterly opposed big parties, the Awami League and the Bangladesh National party (BNP), who have taken turns at running the country in recent decades.

Both parties have been accused of large-scale corruption and abuse of power, in addition to open violence and repression of opponents. Yunus has promised Bangladeshis a “reset”, even describing the student-led uprising as a “second liberation” akin to the 1971 war of independence, when the country wrested its freedom from Pakistan.

Since taking charge, his cabinet — composed largely of technocrats, civil society activists and students — has taken steps to stabilise Bangladesh’s flailing economy. There has also been a partial restoration of order after a period when many policemen quit their posts, fearing public wrath. According to Bangladesh’s police headquarters, however, at least 187 high-ranking law enforcement officials have fled or are missing since the old government’s fall and troops are still helping to help keep order.

Yunus acknowledges that the security situation has “improved a lot, but it’s still not 100 per cent”. The main task of his acting cabinet, he argues, is what it calls a “smooth transition” featuring a reform road map, an economic recovery plan and the enlisting of international support for its efforts. “The whole revolution is about reform,” Yunus says. “We have to reinvent ourselves in a different way.”

Bangladesh’s interim leaders are also pushing for the remaking of state arms like the judiciary and bureaucracy, and for justice for the old regime’s victims.

“Over the last 15 years, they pushed the whole partisan control of institutions to an extreme, on the basis that they thought they would be here for eternity,” says Iftekharuzzaman, the executive director of Transparency International Bangladesh, whom Yunus has tasked with overhauling the country’s discredited Anti-Corruption Commission. “There was a collusion between business, politics and bureaucracy.”

The watchdog, Zaman says, “was always used to protect people in positions of power and to harass and create problems for people who were political opponents or who had fallen from grace”.

Yunus himself fell into the latter category, Zaman adds, after the ACC launched a probe into Grameen Telecom during Hasina’s final years in power that resulted in his conviction of violating labour laws.

Yunus has also appointed Muhammad Nur Khan, a veteran human rights defender, to identify detention centres and secret prisons used by the old regime.

“Before, there were only a few people coming out to say what they had been through,” Khan says in an interview, showing pictures on his phone of one recently uncovered cell — less than seven feet long and three or four wide — with marks on the wall suggesting that prisoners were hung upside-down. Electric shocks and the removal of detainees’ nails were techniques also used, he says.

“If this government continues for at least one year, they can identify the perpetrators behind these crimes,” he adds.

According to Bangladesh’s police, more than 800 people were killed in July and August — although analysts believe that the true number may be as many as 2,000, making this the worst episode of political violence in the country in recent years.

Even so, the situation has not been as dire as Awami League supporters suggested, members of Yunus’s government argue. “If you compare Bangladesh’s post-revolution period to other revolutions like the Arab spring, our situation is much better,” says Asif Nazrul, a former law professor now serving as justice adviser. “And it’s much, much better than what Sheikh Hasina said when she claimed that if the Awami League lost power, every house would be burnt down.”

One property that was burnt down was the Dhaka house museum where Hasina’s father, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, an independence leader, then president and prime minister, was killed in 1975 along with most of his family. In scenes reminiscent of post-Saddam Iraq, protesters also tore down statues of Rahman and “Bangabandhu corners” — shrines to Hasina erected during her last years in power.

An unknown number of Awami League supporters have been arrested, attacked or killed, including some members of Bangladesh’s Hindu minority, who form roughly 8 per cent of the country’s 170mn-plus population. Speaking to the FT, Yunus acknowledges there were a “very small number” of Hindu fatalities, and independent human rights groups have not confirmed large-scale attacks.

Yet the narrative of Hindus being slaughtered has taken hold in India and soured relations with Narendra Modi’s government. Awami League officials now in hiding or exile claim many of their supporters have been targeted. “The state tortured and killed thousands and thousands of party members after August 5 around our country,” Khalid Mahmud Chowdhury, a former Awami League minister and MP, says in a phone interview.

Chowdhury also lambasts remarks made by Yunus in a Voice of America interview, where he referred to pressing a “reset button” in politics. “Pushing the reset button means you have to erase the history of the liberation, of the war, and erase the past,” he says. “The people will not allow them to.”

Nazrul, Yunus’s justice adviser, dismisses the claim about “thousands and thousands” of killings and arrests as an “absolute lie”. “They stole almost all the wealth of our country,” he says. “Now they are using their wealth, their international lobbying and their strong vested interest network to spread lies and to discredit this government.”

Even so, NGOs do confirm there have been attacks and other acts of retribution, notably by members of the BNP, some of whom were victimised during Hasina’s rule. “BNP political leaders . . . are trying to implicate Awami League people in criminal cases,” says Jyotirmoy Barua, a human rights lawyer. “It’s a good way of extortion.”

Student activists have also wielded power in ways critics have found questionable. In one incident early in October, a group of about 300 people gathered at the Supreme Court and presented a list of judges they saw as politically tainted; about a dozen were subsequently sent on leave. This echoed events in August, when a student-led crowd broke into a courtroom and forced the then chief justice Obaidul Hasan to step down.

“Students should not be coming into the courtroom demanding the resignation of judges,” says Barua. “It’s not their job.”

As Yunus and his advisers attempt to meet the protesters’ expectations against a ticking clock, numerous pressures are building. One vulnerable point is the economy, which was already suffering because of its reliance on imported fuel and commodities during a period of steep global inflation.

Directly after the recent unrest, prices spiked as the breakdown in security frayed supply chains, exacerbated by seasonal flooding. Central bank governor Mansur has presided over three interest rate hikes since August, raising the benchmark policy rate from 8.5 per cent to 10 per cent. To prop up the taka, the Bangladesh Bank also stopped selling dollars.

The country’s foreign exchange reserves now stand at just below $20bn: still precarious, equivalent to about four months’ of imports, but no longer declining. “The current account for the last two months is in surplus — a small surplus, but welcome,” says Mansur.

In a recent report, Fitch Ratings wrote that “if reforms are pursued and governance standards improve”, Bangladesh’s credit rating could rebound after being downgraded earlier in the year.

In the real economy, garment industry bosses are working to win back the confidence of high-street chains, some of which diverted orders to India, Vietnam or elsewhere.

Some BNP members are pressing for elections to be held soon; many in the party believe they will win easily, even if a dispersed and dissipated Awami League is allowed to stand again.

However, one senior BNP official endorsed Yunus’s drive to reform Bangladesh’s compromised institutions first. “We are giving them reasonable time to implement fundamental reforms,” says Amir Khasru Mahmud Chowdhury, a member of the party’s standing committee.

Although Yunus insists Bangladesh’s future political space will be decided by the parties themselves — and declares fealty to none himself — the BNP is widely seen as ascendant in the new dispensation. Meanwhile, mining a contacts book that features some of the world’s most powerful people, the chief adviser has won support from multilateral lenders and western governments.

Yet perils lie ahead. Some Bangladeshis privately voice concerns that Yunus is too indulgent of the students, entrusting key decisions on the country’s future to 20-somethings giddy with newfound power. Others argue that, if entrenched interests torpedo reforms or the two main parties choose to reassert themselves, he and his team may fail to accomplish their goals.

If Yunus himself is worried, he shows no sign. Bangladesh’s temporary leader will not be pressed on an election date — and when prompted, insisted that “revolution” is the correct word for what he and his colleagues are doing.

“When parliamentary democracy fails, there is room for a revolution,” he says. “And that’s what happened here.”

Additional reporting by Zia Chowdhury in Dhaka.

-20260225072312.webp)

-20260224075258.webp)

-20260219054530.webp)

-20260218060047.jpeg)