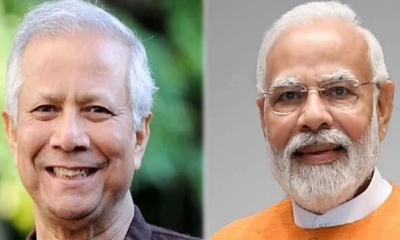

Today, they are two of the most powerful executives in the tech industry’s race to build artificial intelligence. Hassabis, 47, is CEO of Google DeepMind, the tech giant’s central research lab for artificial intelligence. Suleyman, 39, was recently named CEO of Microsoft AI, charged with overseeing the company’s push into AI consumer products.

Their path from London to the executive suites of Big Tech is one of the most unusual — and personal — stories in an industry full of colourful personalities and cutting rivalries. In 2010, they were two of the three founders of DeepMind, a seminal AI research lab that was supposed to prevent the very thing they are now deeply involved in an escalating race by profit-driven companies to build and deploy AI.

Their paths diverged after a clash at DeepMind, which Google acquired for $650 million in 2014. When the AI race kicked off in late 2022 with the arrival of the ChatGPT online chatbot, Google put Hassabis in charge of its AI research. Suleyman took a rockier route — founding another AI startup, Inflection AI, that struggled to gain traction before Microsoft unexpectedly hired him and most of his employees.

“We’ve always seen the world differently, but we’ve been aligned in believing that this is going to be the next great transition in technology,” Suleyman said of his old family friend in an interview. “It is always a friendly and respectful rivalry.”

Microsoft’s push into artificial intelligence with its partner, OpenAI, the maker of ChatGPT, has rattled Google. The two companies are now fighting to control what many experts see as the next dominant computing platform, a battlefield as important as the web browser and the smartphone before it. Hassabis is driving the creation of Google’s AI technology, while Suleyman works to put Microsoft’s AI in the hands of everyday people.

Though Suleyman sees their relationship as a cordial rivalry, Hassabis believes any talk of rivalry is overblown. He does not see Suleyman as a major threat, because competition in AI was already so high, with so many formidable companies.

“I don’t think there is much to say,” he said in an interview with The New York Times. “Most of what he has learned about AI comes from working with me over all these years.”

When the two first met, Suleyman was in grade school and Hassabis had started a computer science degree at the University of Cambridge. While Hassabis was competing in the annual Varsity Chess Match between Cambridge and Oxford, his younger brother, George, and Suleyman were teaching chess to local children at a Wednesday night math school run by the Hassabis family in North London.

Suleyman later studied philosophy and theology at Oxford, before dropping out to help start a mental health helpline for Muslim teenagers and working as a human rights officer for the mayor of London. Hassabis founded a video game company, before returning to academia for a doctorate in neuroscience. But they shared an interest in high-stakes poker. “We are both quite good,” Suleyman often says.

In 2010, after sitting down for a game at the Victoria Casino in London, they discussed how they could change the world. Hassabis dreamed of building technologies of the future. Suleyman aimed to change society right away, improving health care and closing the gap between the haves and the have-nots.

“Demis had the pure-science moonshot aspiration,” said Reid Hoffman, a Silicon Valley venture capitalist and Microsoft board member who helped found both OpenAI and Suleyman’s Inflection AI. “He convinced Mustafa this science could be a high-order bid for making things better for society — for humanity.”

Hassabis was finishing postdoctoral work at the Gatsby Computational Neuroscience Unit, a University College London lab that combined neuroscience (the study of the brain) with AI (the study of brainlike machines). Seeing Suleyman as a hard-charging personality who could help build a startup, he invited him to the Gatsby for meetings with a philosophically minded AI researcher, Shane Legg. In the afternoons, they would huddle at a nearby Italian restaurant, cultivating a belief that AI could change the world.

By the end of 2010, after engineering a meeting with Peter Thiel, a Silicon Valley venture capitalist, the three of them had secured funding for DeepMind. Its stated mission was to build artificial general intelligence, or AGI, a machine that could do anything the human brain can do.

They were also determined to build the technology free from the economic pressures that typically drive big business. Those pressures, they believed, could push AI in dangerous directions, upend the job market or even destroy humanity.

As Hassabis and Legg (who is still with DeepMind) pursued intelligent machines, it was Suleyman’s job to build products and find revenue. He and his team explored an AI video game, an AI fashion app and even whether AI could help a company, Hampton Creek, making vegan mayonnaise, a former colleague said.

Hassabis told employees that DeepMind would remain independent. But as its research progressed and tech giants such as Facebook swooped in with millions of dollars to poach its researchers, its founders felt they had no choice but to sell themselves to Google. DeepMind continued to operate as a largely independent research lab, but it was funded by and answered to Google.

By the end of 2010, after engineering a meeting with Peter Thiel, a Silicon Valley venture capitalist, the three of them had secured funding for DeepMind. Its stated mission was to build artificial general intelligence, or AGI, a machine that could do anything the human brain can do.

They were also determined to build the technology free from the economic pressures that typically drive big business. Those pressures, they believed, could push AI in dangerous directions, upend the job market or even destroy humanity.

As Hassabis and Legg (who is still with DeepMind) pursued intelligent machines, it was Suleyman’s job to build products and find revenue. He and his team explored an AI video game, an AI fashion app and even whether AI could help a company, Hampton Creek, making vegan mayonnaise, a former colleague said.

Hassabis told employees that DeepMind would remain independent. But as its research progressed and tech giants such as Facebook swooped in with millions of dollars to poach its researchers, its founders felt they had no choice but to sell themselves to Google. DeepMind continued to operate as a largely independent research lab, but it was funded by and answered to Google.

For years, DeepMind employees had whispered about Suleyman’s aggressive management style. That came to a head in early 2019 when several employees filed formal complaints accusing Suleyman of verbally harassing and bullying them, six people said. Former employees said he had yelled at them in the open office and berated them for being bad at their jobs in long text message threads.

Suleyman later said of his time at DeepMind: “I really screwed up. I remain very sorry about the impact that that caused people and the hurt that people felt there.”

He was placed on leave in August 2019, with DeepMind saying he needed a break after 10 hectic years. Multiple people told Hassabis that the punishment should go further, two people with knowledge of the conversations said.

Months later, Suleyman moved into a job at Google’s California headquarters. Privately, Suleyman felt that Hassabis had stabbed him in the back, a person with knowledge of their relationship said.

Suleyman’s new Google position had a big title — vice president of AI product management and AI policy — but he was not allowed to manage employees, two people said. He disliked the role, a friend said, and soon left to start Inflection AI.

When OpenAI released ChatGPT less than a year later, sparking an industrywide race to build similar technologies, Google responded forcefully. Last April, the company merged its homegrown AI lab with DeepMind and put Hassabis in charge.

(The New York Times sued OpenAI and Microsoft in December for copyright infringement of news content related to AI systems.)

For a time, Suleyman remained an independent voice warning against the tech giant and calling for government regulation of AI. An opinion piece that he wrote with Ian Bremmer, a noted political scientist, argued that big tech companies were becoming as powerful as nation-states.

But after raising more than $1.5 billion to build an AI chatbot while pulling in practically no revenue, his company was struggling. In March, Inflection AI effectively vanished into Microsoft, with Suleyman put in charge of a new Microsoft business that will work to inject AI technologies across the company’s consumer services.

Suleyman, who splits his time between Silicon Valley and London, officially became a rival to Google DeepMind, opening a new Microsoft office in London to compete for the same talent. Hassabis expressed frustration to his staff that Suleyman was positioning himself as a prominent AI visionary, a colleague said.

They still text each other on occasion. They might meet for dinner if they are in the same city. But Hassabis said he does not worry much about what Suleyman or any other rival is up to.

“I don’t really look to others for what we should be doing,” Hassabis said.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

-20260222063838.webp)

-20260206050656.webp)