Countries are being urged to strengthen their carbon-cutting targets by the end of 2022 in a draft agreement published at the COP26 Glasgow climate summit.

The document says vulnerable nations must get more help to cope with the deadly impacts of global warming.

It also says countries should submit long-term strategies for reaching net-zero by the end of next year.

Critics have said the draft pact does not go far enough but others welcomed its focus on the 1.5C target.

The document, which has been published by the UK COP26 presidency, will have to be negotiated and agreed by countries attending the talks.

Analysis

Some comfort for developing countries:

The document may be just seven pages long but it attempts to steer COP26 towards a series of significant steps that will prevent global temperature rises going above 1.5C this century.

Perhaps the most important part of that is getting countries to improve their carbon cutting plans.

To that end this draft decision urges parties to "revisit and strengthen the 2030 targets in their nationally-determined contributions, as necessary to align with the Paris Agreement temperature goal by the end of 2022".

It will be interesting to see how countries such as China, India, Brazil and Saudi Arabia respond to this request to put new plans on the table by the end of next year.

There is some comfort for developing countries to see that their financial needs are recognised as countries are asked to mobilise climate finance "beyond $100bn a year" and the draft welcomes steps to put in place a much larger, though as yet unspecified, figure for support from 2025.

Loss and damage, an issue of key importance to the developing world, is included in the draft with encouragement to richer countries to scale up their action and support including finance for poorer nations.

The document also calls on countries to accelerate the phase out of coal and subsidies for fossil fuels - but has no firm dates or targets on this issue. Campaigners will welcome the inclusion and will hope it survives into the final text.

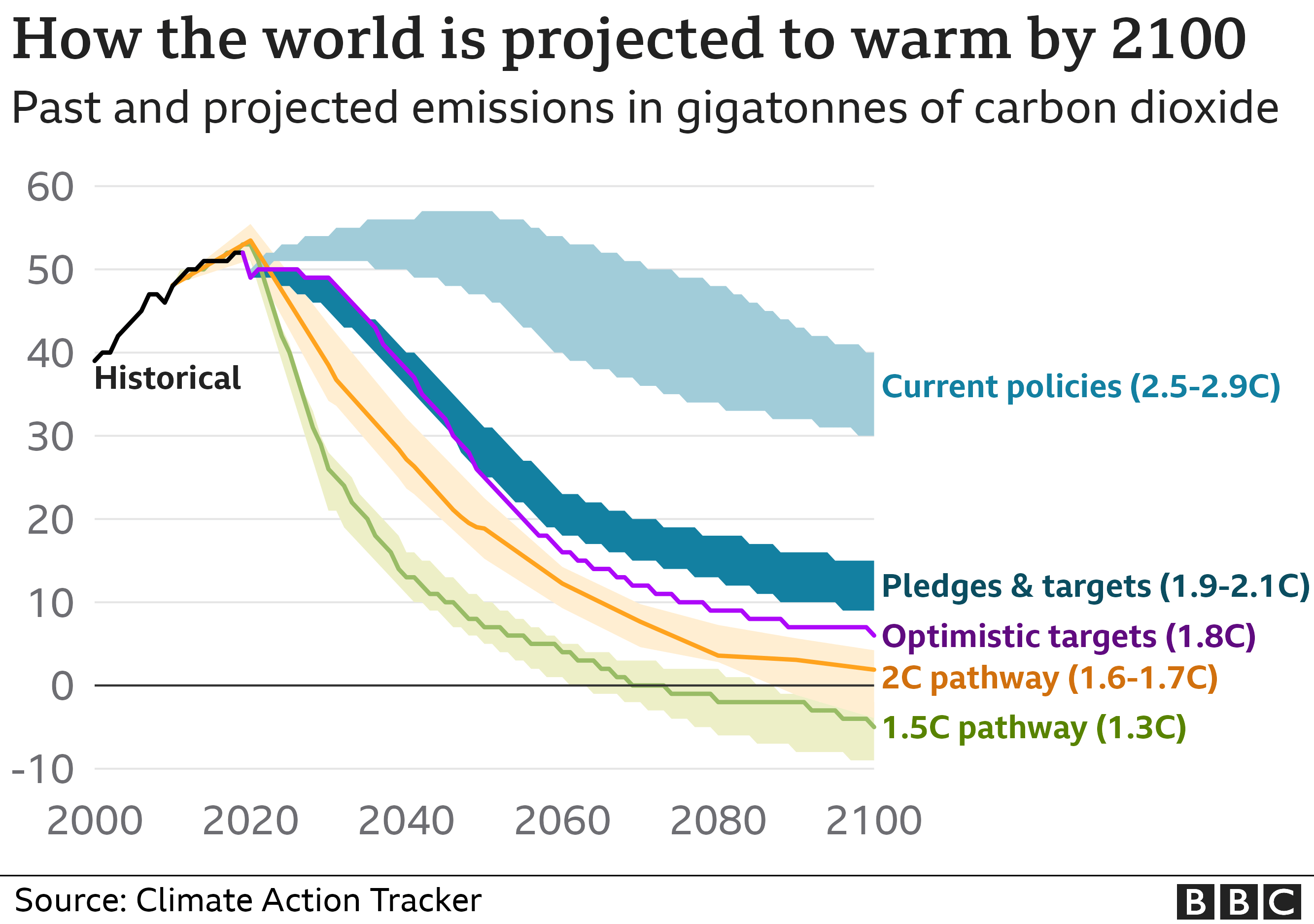

Scientists have warned that keeping temperature rises to 1.5C - beyond which the worst impacts of climate change will be felt - requires global emissions to be cut by 45% by 2030 and to zero overall by mid-century.

The draft agreement proposes an annual high-level ministerial meeting, beginning at next year's COP conference, likely to be in Egypt, to discuss goals for reaching the 2030 target.

To further underline the importance of the 2030 target, the document also asks UN secretary general Antonio Guterres to convene world leaders in 2023 to consider how efforts are shaping up.

It emphasises the "critical importance" of nature-based solutions, including protecting and restoring forests to reduce emissions, absorb carbon and protect biodiversity.

David Waskow, from the World Resources Institute, said there would be opposition to the idea of coming back with new plans next year from a range of countries.

"On the question of the revisiting and strengthening of targets, there are certainly parties who have been pushing back, the Saudis and Russians have been quite clear on that, others have been less blunt," he said.

"The other countries who are pushing back are many of the vulnerable countries, who don't comprise that large percentage of global emissions often or have very limited resources to develop nationally-determined contributions and then to implement them."

'Cross our fingers and hope'

Loss and damage - an issue of key importance to the developing world - has been included in the draft, calling for more support from developed countries and other organisations to address the damage caused by extreme weather and rising seas in vulnerable nations.

It also recognises that more finance is needed for developing countries beyond the long-promised $100bn a year by 2020, which will not be delivered until at least 2022.

But campaigners said these parts of the text were weak and were essentially a "box ticking exercise".

The document also calls on countries to accelerate the phasing out of coal and subsidies for fossil fuels - but has no firm dates or targets on this issue.

"This draft deal is not a plan to solve the climate crisis, it's an agreement that we'll all cross our fingers and hope for the best," said Jennifer Morgan from Greenpeace International.

Labour's shadow business secretary Ed Miliband said Prime Minister Boris Johnson needed to "take charge of a summit that is not on track to deliver".

"We are miles off where we need to be in the halving of emissions required by 2030," he said.

"It's time the government faced this truth, stopped the greenwash, and put maximum pressure on all parties to step up and agree a path out of Glasgow to keep 1.5 alive."

Source: Climate Action Tracker/BBC

The World Wide Fund for Nature said the call for enhanced 2030 targets and references to phasing out fossil fuel subsidies, among other proposals, "must stick".

Manuel Pulgar-Vidal, WWF Global Lead Climate & Energy said: "With the world still on course for dangerous global warming, it is essential that ministers work to include a clear plan to close the 2030 ambition gap and the timeframe to do this.

"It is clear that there is more to be done, and negotiators must improve the areas of the text that are still weak. This must be a floor, not a ceiling."

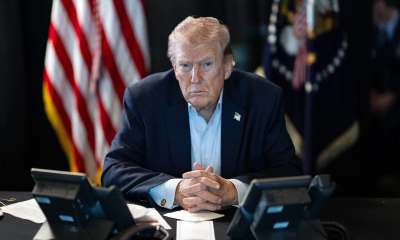

The prime minister is returning to COP26 later.

On Wednesday, Mr Johnson spoke with the crown prince of Saudi Arabia about the country's climate pledges and the need to make "progress in negotiations" taking place in Glasgow, No 10 said.

Saudi Arabia was among a number of countries asking the UN to play down the need to move rapidly away from fossil fuels, according to leaked documents.

A Downing Street spokesman said: "They discussed the importance of making progress in negotiations in the final days of COP26, including on finalising the outstanding elements of the Paris rulebook.

"The prime minister said all countries needed to come to the table with increased ambition if we are to keep the target of limiting global warming to 1.5C alive."

Research published at the summit on Tuesday indicated the short-term plans put in place by countries would see a rise of 2.4C.

While about 140 nations have pledged to reach net zero emissions by around the middle of the century, scientists have said their short-term plans for 2030 are not strong enough to limit the rise in temperatures.

-20260308122356.webp)

-20260308071814.webp)

-20260309130627.webp)

-20260309114959.jpg)

-(1)-20260308145648.jpg)

-20260303080739.webp)